Inside the community that experienced America’s first major school shooting of 2018

By Helen Gibson

Darkness covered Mike Miller Park in Benton, Kentucky, on the evening of Thursday, Jan. 25, but the lights from their candles illuminated the spaces between them. Children, teenagers and adults held these candles in their hands as they sang songs and prayed, hugged one another and cried.

A musician strummed a guitar and sang the words to a contemporary worship song, and the crowd of people raised their candles in the air, letting them flicker in the darkness. Local news outlets would later report that there were around 1,000 people present at this prayer vigil — students, parents, community members, mourners.

Parker Jennings, a Marshall County High School senior, stepped behind the microphone and addressed the crowd that had gathered on the large soccer field.

“The past two days have been the hardest two days of my life,” Jennings said in his unmistakable Southern twang. The air was cold — so much that Jennings could see his own breath as he spoke.

It had only been about 60 hours since the tragedy Jennings was referring to, and the memories were still fresh in his and his classmates’ minds.

At 7:57 on the morning of Tuesday, Jan. 23, Marshall County students waiting for their first classes to start heard gunshots ring out from the commons area of their high school. Two 15-year-old students were killed, Bailey Holt and Preston Cope. At least 18 others were injured by gunshots or the chaos that ensued. Their classmate, 15-year-old Gabriel Ross Parker, a sophomore, was arrested minutes later and charged with two counts of murder and 12 counts of first-degree assault.

News of this event traveled quickly in this rural, tight-knit county of just over 31,000, and it sent shockwaves around the state and made national news headlines. It was the first major U.S. school shooting of 2018, though another even more deadly shooting in Parkland, Florida, would soon eclipse it, sparking national conversations about gun reform.

But that cold, January night at the prayer vigil in the park, Marshall County residents were only focused on one tragedy: their own. And it would stick with them in the days, weeks and months to come.

Marshall County senior Cameron King was one of the faces in the crowd that night. After fleeing the high school in her blue Toyota Corolla on the morning of Jan. 23, she’d spent the last two days surrounded by friends as often as she could. It was in her moments alone that the memories flooded back.

“I remember just laying in bed and just crying,” King said later, reflecting on those first few days in the wake of the tragedy. “Every little thing would make me so sad.”

Despite the 40-degree weather, King said she and her friends stayed for about an hour after the prayer vigil ended — “hugging everybody, [saying] I love you and just crying on each other,” she said.

As they poured out of the park and onto the two-lane stretch of Highway 68 that led into Draffenville, the headlights of their cars shining bright, they created so much traffic that Marshall County officials had to request a traffic alert, according to the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet.

But King said the large turnout and show of support on the soccer field that night — the night before she and her classmates would return to school for the first time since the shooting — was worth it.

“It was just a way for the community to come together, be one little unit and heal together,” King said. “It was the first step toward healing.”

A community coming together

Over the next few weeks, various Marshall County residents said they saw the community come together as it never had before.

On the evening of Friday, Feb. 2, eight days after the prayer vigil and 10 days after the school shooting, members of a worship band stood atop a small stage in a multipurpose room at Trace Creek Baptist Church in nearby Mayfield, Kentucky. They were preparing for a benefit concert that would be held a couple weeks later, organized by Marshall County native Jake Petway.

Petway, a 32-year-old software engineer, wore a blue and white Marshall County hat turned backward and a royal blue and bright orange checkered shirt — the school colors of Marshall County.

He said the shooting at his alma mater was “the single worst day” he could remember as a Marshall County native.

“I’ve personally been through some dark days,” Petway said as his band members tuned their instruments and warmed up. “But I can’t remember a day that I experienced that much fear.”

The afternoon of the shooting, he and his wife started organizing a benefit concert that would be held a few weeks later to raise money for the families of the victims, he said.

“My wife and I got to talking, and we just didn’t feel like posting ‘thoughts and prayers’ like everybody does was adequate — at least not for us,” Petway said.

When it was held, the concert ended up raising over $6,000.

The same night of Petway’s band practice in Mayfield, Bluegrass musicians hosted a similar benefit concert at the Kentucky Opry in Benton. At that show, volunteers took up over $3,500 in donations for the families of the shooting victims, said Jason McKendree.

McKendree, president of a local Bluegrass organization and a 1999 graduate of Marshall County High School, helped organize the event. Like many in his community, he said he wanted to do something to support those who had been affected firsthand.

“I think just everyone [has been] trying to think in what ways they could help out,” McKendree said.

The next day — a cold and cloudy Saturday morning in western Kentucky — various other fundraisers took place across Marshall County and in nearby communities, including a vendor fair in downtown Paducah and live music, drinks and food at Dam Brewhaus, a relatively new craft brewhouse in Benton. The event at Dam Brewhaus alone raised over $7,000 for the families of the victims, according to a Facebook post.

Across town, reminders of the recent tragedy were easy to spot. Blue and orange ribbons were tied to mailboxes and the front doors of homes. Removable letters on signs outside of schools and churches spelled out “Marshall Strong.” This phrase, along with several different Bible verses, was painted onto the windows of shops in the tiny town square of Benton, Marshall County’s county seat.

Just after 4 o’clock on the afternoon of Saturday, Feb. 3, people filled The Pond, a family-owned catfish restaurant in nearby Aurora that has been open in some capacity for over 50 years. The tables were filled, and several families sat on wooden benches in a waiting area at the front of the restaurant.

At the cash register, a hostess took cash for blue T-shirts with the words “Marshall Strong” printed on the front. She also sold similar bracelets and key chains.

All the proceeds from today’s restaurant sales were going to the victims of the school shooting, said Heather Wyatt, who co-owns the restaurant with her husband, Jeremy Wyatt.

The Wyatts knew firsthand some of the fear that came along with a school shooting. Their son, 15-year-old Kobe Wyatt, a freshman, had stood just 100 feet away from the spot where shots were fired on the morning of the shooting, Heather Wyatt said. Unlike some students, however, Kobe Wyatt walked away uninjured.

As soon as they learned he was safe, Heather Wyatt said she and her husband, like many community members, started thinking of ways they could help. To them, a fundraiser at the restaurant seemed like the best option.

When asked about the day of the shooting, Heather Wyatt gave a long pause, and she looked upward. Tears welled up in her eyes, and she tried to blink them away, still looking at the ceiling. They started running down her cheeks, and she brushed her index fingers across her face to wipe them away.

She wasn’t ready to answer that question, she said.

It had been 11 days, but for her, the pain was still too fresh.

Changes at Marshall County High School

In the aftermath of the school shooting, administrators at Marshall County High School started taking measures to make the school safer than it had been before.

Six days after the shooting, the school district sent a message to parents, informing them that school officials would start limiting the number of ways students could enter the building each morning. Before, junior Keaton Conner said students could use any door, but now, they would be required to enter through one of four unlocked doors, where a staff member would greet them and search their bags for any suspicious objects, according to the statement.

The statement also said any student arriving after 8:03, three minutes after the school’s official start time, would be required to check in with the front office.

A week later, school officials sent another message to parents — this time informing of new metal detector wands at each entrance. On Tuesday, Feb. 6, staff members would start screening students with these before allowing them to enter the school building.

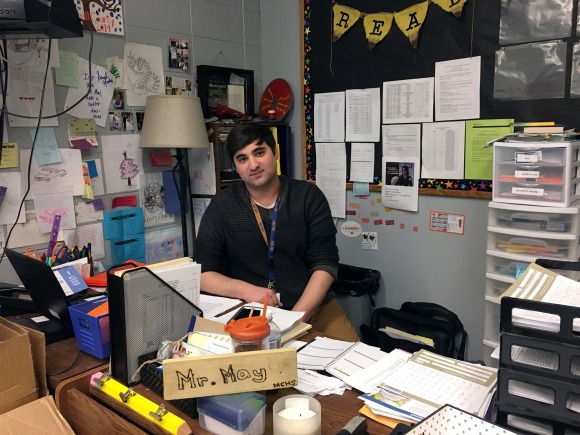

Sophomore English teacher Ethan May said these measures made the school feel safer for both students and faculty members.

“They complain, ‘it makes me late,’ and things like that, but they do feel safer,” May said. “And they’ve expressed that on more than one occasion.

However, Marshall County Sheriff Kevin Byars knew he wanted to do more.

Byars had rushed to the high school on the morning of the shooting, and he ended up leading Gabe Parker, the alleged shooter, off the school property in handcuffs. As he spoke about the events of that day even weeks later, it was evident that he was still disturbed by what he’d seen.

“Here, we’re close-knit,” Byars said. “We all know each other. We grew up here. So I knew the families of the injured, knew the families of the ones that were killed.”

Prior to the school shooting, there’d been only one school resource officer for all seven Marshall County Schools, meaning the officer had to float between each of the different schools. Following the shooting, Byars said he put a second officer on duty at Marshall County High School, at the request of school officials. He also began working with school officials to submit grant proposals to bring more school resource officers into Marshall County schools — something he said he’d been wanting to do for a long time but hadn’t been able to accomplish because of budget constraints.

Byars hoped to secure enough grant money to fund four additional school resource officers. If he was able to, he said he’d place a total of two at the high school, one at each of the two middle schools and one as a floater between the middle schools and the four elementary schools in the county.

“If there was an unlimited pot of money, that’s exactly how I would set it up,” Byars said.

Another tragedy

Streetlights illuminated the dark in Benton’s small town square on the evening of Thursday, Feb. 15. It was 23 days after the school shooting that had shaken this community, and now, nearly 100 people gathered in the street. Some held candles, and others grasped onto homemade signs with phrases like “sending love and prayers” and “we stand with Stoneman Douglas High School” written on them. Many were dressed in orange and blue Marshall County T-shirts.

The day prior, another school shooting had made national headlines — this time, at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. Seventeen people were killed when police said a former student, 19-year-old Nikolas Cruz, walked into the school and opened fire.

In Marshall County, this news hit close to home.

Cameron King said she was headed to speech practice when she saw a Washington Post notification on her phone, informing her of the shooting at Stoneman Douglas.

“I thought, ‘Oh my god, not again,’” King said. “Like, this literally just happened.”

She said the news that another school had endured a shooting just weeks after the tragedy at her school was hard to believe.

“It was so soon,” King said. “I mean, we hadn’t even turned on the bells at school yet. We hadn’t turned the bells on. You couldn’t go to the bathroom without being escorted there. We still had counselors at school. And we were just like, we haven’t even had time to heal, and this happens to someone else, and now they’ve gotta go through the same thing we are.”

She said she and a couple of her friends on the speech team couldn’t hold back their tears that afternoon.

“Every time I hear about these things, I just break down because it’s so personal,” King said.

For many students, teachers and community members, news of the shooting in Florida reminded them of what they’d lost three weeks earlier, said Ethan May.

“It was like we were in day one again from our own tragedy,” May said.

Rachel Lane, a paramedic who’s spent most of her life living in Marshall County, said she didn’t start to fully realize what had happened in Florida until about 8 o’clock that night. That’s when she began to organize the prayer vigil that would be held the following evening in the town square.

“I feel like God just placed it on my heart [to organize this event] because we have leaned so much on our faith in God in this community,” said Lane, who volunteers with students at her church, New Zion Missionary Baptist. Many of these students, she said, were still struggling to cope with effects of the shooting that had taken place at their own high school.

At the vigil on Thursday night, the people who gathered in the town square grabbed hands with one another, and they bowed their heads to pray. Now, Lane said, they were praying for strength and healing for the Stoneman Douglas students and community members, as well.

“We’re bringing these two communities together,” Lane said.

Mixed feelings

In the days following the shooting in Parkland, some Stoneman Douglas students began making headlines for their advocacy efforts.

Emma Gonzalez, a Stoneman Douglas senior, famously called BS on politicians and gun rights activists; she gained nearly a million Twitter followers in a week. Several other Stoneman Douglas students engaged with the media and raised millions of dollars through GoFundMe and private donations from celebrities, according to CNN.

Their efforts were not met without backlash. Leslie Gibson, a Republican candidate for Maine’s House of Representatives, referred to Gonzalez a “skinhead lesbian” on Twitter and called David Hogg, another Stoneman Douglas senior, a “moron” and a “baldfaced liar,” according to the New York Times.

Online, some others claimed the student activists were crisis actors paid to further an “anti-gun agenda” and that they were “coached, left wing puppets,” according to Vox.

Still, just four days after the tragedy, a group of Stoneman Douglas students announced plans for March for Our Lives, a demonstration in Washington, D.C., in which they would protest against gun violence.

To some Marshall County residents, the reactions of students at Stoneman Douglas seemed very different to what they’d seen in their own community, where guns are a normal part of life.

On a warm and sunny Saturday in Mike Miller Park in early March, people from Marshall County and communities around the region gathered for a car show fundraiser that raised over $2,000 for those affected by the school shooting, according to the Facebook event page.

As groups of people strolled around, stopping to look at vintage cars and say hello to neighbors and friends, they discussed what had become a common topic since Jan. 23: school shootings.

Fifty-year-old Lisa Tally criticized the Parkland community for not coming together the way she’d seen her community do.

“They’re not doing near what our small community has done,” Tally said. “They’re just pointing the finger at each other. It’s crazy. And the kids are marching against guns and stuff. Why are kids marching against guns? That doesn’t make sense to me. It just doesn’t.”

Nearby, a group of women — Kaitlyn Roberts, Sherry Roberts and Kimberly Duncan — stood around a bright orange Ford Mustang with strips of blue painter’s tape running down the middle. As they spoke, they seemed to agree that school shootings shouldn’t lead to increased restrictions or regulations on guns.

“I don’t think it’s the gun’s fault,” Duncan said. “I think it’s the same as people who drive drunk. It’s not the car’s fault.”

Kaitlyn and Sherry Roberts nodded their heads and voiced their agreement.

“I don’t think there’s a bill that you could pass that’s going to fix the problem,” Duncan said.

“No, I don’t think it either,” Sherry Roberts said. “You know, I’m old school. It stems with how you’re raised and having a good, solid foundation and values and things like that.”

Sherry Roberts said she thought school shootings could be attributed to problems that started at home. She said some children were simply no longer raised in homes where they felt loved.

“I wish there was a bill that could be passed that would fix it, but there’s not,” Duncan said.

“I do, too,” Sherry Roberts said.

“I mean, I think the thing about gun control is it’s just a diversion away from the issue,” Duncan said.

As these women stood in a circle and shared their opinions with one another, their comments were reminiscent of those from Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin, who, the week of the Marshall County shooting, said that school shootings were “a cultural problem,” spurred on by video games, movies, TV shows and song lyrics.

To these women and many others in Marshall County, increased gun regulations like those that were being advocated for by some Stoneman Douglas students wouldn’t do anything to solve the real problem.

But, that wouldn’t stop a small but impassioned group of Marshall County students from trying to make a change.

Not enough

Sixteen-year-old Keaton Conner, a junior at Marshall County High School, said seeing Stoneman Douglas students speak out and advocate for change forced her to start rethinking the way she’d reacted to the shooting at her own high school.

“It was terrible and it was the worst day of my life, but immediately after, my response wasn’t what I wish it had been,” Conner said. “You know, the way these students in Florida have taken all of their grief and pushed it into making a change is something that I can’t help but think, if we would have done that would [a school shooting] have happened to them?”

As she sat at a tall, wooden table at a local bakery in Benton and recalled the events that had taken place since the Marshall County school shooting, Conner said advocating for increased school safety and gun regulation is something she’d started to become passionate about.

“I think now that I’ve had this realization, I don’t think that I’ll be able to be happy until I know that I’ve done all that I can do.”

Conner’s friend Cameron King echoed her sentiments. King said she was a proponent of increased gun regulation even before Jan. 23, but she almost felt like it took another school shooting for some members of her community to see what was really at stake.

“I think that’s kind of what we needed here to jump start a lot of things too,” King said.

She went on to say she saw certain differences between her county and the city of Parkland, though. She thought this might be part of the reason the two communities responded to their respective school shootings so differently.

“They’re just in a bigger community,” King said of Parkland, Florida. “They’ve got more diversity there. They’ve got more types of people who are willing to break the boundaries and step forward, whereas here I feel like there are a lot of people that have just gone with the flow … They’re just like, ‘Oh, we’re a small town. We can’t do anything.’”

At the same time as Marshall County residents were reckoning with the reality of gun violence in schools, President Donald Trump was meeting with various officials in regards to this issue.

On Thursday, Feb. 22 — eight days after the Stoneman Douglas shooting and 30 days after the Marshall County shooting — President Trump met with Kentucky State Police Chief Rick Sanders, as well as Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi and Parkland mayor Christine Hunschofsky to discuss school safety.

A week later, Sheriff Byars was invited to the White House to discuss the same issue.

It was a cloudy, rainy day in Washington, D.C., when Byars sat around the table in the Roosevelt Room with a group of people from around the country who, like himself, had firsthand experience with school shootings. He remembered President Trump walking in, sitting down at the table and asking the group who had gathered to share their thoughts on how to increase the safety of schools nationwide and prevent future gun violence.

The following day, Byars said he left the meeting feeling like their conversation had been “well worth it.”

“It seems like this administration does want to help [solve] the problem,” Byars said. “How they go about it, I don’t know yet, but they seem genuinely concerned.”

While Byars continued to advocate for grants to fund more school resource officers, other Marshall County officials didn’t want to wait on the possibility of grant money; they called for immediate change. Such was the case for Marshall County Judge Executive Kevin Neal.

On March 13, Neal released a plan for increased security at Marshall County High School. It included hiring six school resource officers independent from the sheriff’s office, purchasing permanent metal detectors, further limiting entry points to the school and building a new sheriff’s office on the school’s campus, so additional law enforcement officials would be nearby in the event of another school shooting.

In his statement, Neal recommended delaying some of the $13.3 million in school renovations officials had been planning to undertake over the summer. Instead, he suggested using some of those funds to implement immediate change, as detailed in his plan.

“Stop this waiting game,” Neal wrote in the statement. “… This tragedy can happen again. We must not try to convince ourselves otherwise. Fortunately, we can dramatically decrease the chances. The time is now.”

Three days later, Marshall County Schools superintendent Trent Lovett issued a statement, assuring community members that increased safety measures were being taken and that school officials were looking into ways to make the school even safer.

But students like King and Conner wanted to see more than just increased school safety. They acknowledged the fact that they already felt safer in their school than they had before the shooting. Now, they wanted to see gun laws change.

“We need to make sure nobody can get their hands on these types of weapons,” Conner said. “You know, you can only do so much as far as security things. There has to be some sort of law in place that makes sure this never happens again.”

They started working with friends from Marshall County and with groups of students from across the state on various events they hoped would shine a light on the issue of gun violence in schools.

Conner and King weren’t the only ones who had been inspired by the activism of the Stoneman Douglas students who had begun speaking out.

Heather Adams had watched her son, Seth, a freshman at Marshall County, struggle with anxiety and panic attacks after he witnessed the shooting at his high school back in January.

“And then, that shooting happened at [Stoneman Douglas], and that was enough,” Heather Adams said. “We had to do something.”

She said this led her and a group of others to start planning a March for Our Lives event in Marshall County, which would function as one of over 800 “sibling marches” to the one Stoneman Douglas students were organizing in Washington, D.C.

For them, it was time to take action.

Taking action

On Wednesday, March 14, before the sun rose, a group of Marshall County High School students gathered in their school parking lot and then climbed onto a charter bus and headed toward the state Capitol in Frankfort. Seth Adams, Keaton Conner and Cameron King were just a few of these students; they were joined by around 37 of their classmates.

They drove 238 miles, and when they arrived in Frankfort, they joined hundreds of students from high schools across the state, who’d gathered to lobby for increased safety in schools. Conner and the other students who helped organize the event described it as an apolitical demonstration.

The sun shone down on the state Capitol steps, which were wet from snow that had recently melted. At 31 degrees, the air and wind were cold on the students’ exposed hands and faces.

“I can’t feel my feet,” one high school boy said to his teacher as she walked by.

“No one forced you to come,” she reminded him.

In the minutes before the rally was set to begin, the students who had gathered fielded questions from reporters, held their signs high and occasionally broke out in chants — repeating phrases like “No more silence, end gun violence” and “enough is enough.” Their voices rang out.

“Our teachers, they prepare us for a lot of things — college, the ACT, going into the workforce,” Conner said, as students in the crowd listened along. “Our parents, they prepare us for the future. They prepare us for life in general. That is, if we are one of the ones to make it past high school.”

She continued, remembering the events of Jan. 23 — the horrific day when a shooter opened fire in her high school, killing two classmates and injuring more than 18 others.

“But no one prepares us to run for our lives,” Keaton said. “No one prepares us to lose every ounce of safety we have. No one prepares us to take on a fight that has been pushed aside since before we were born. No one prepares us to deal with the hatred of those who try to silence us.”

Later, as another speaker stood behind the microphone and issued a rallying cry of her own, Keaton walked down a few of the steps to the spot where her father, Troy Conner, stood among other demonstrators. Troy, who had recorded Keaton’s speech from his iPhone, wore a thick, black North Face jacket. He wrapped his arm around his daughter and pulled her in close — something some parents could no longer do.

Marching on

Two weeks later, early on the drizzling, rainy afternoon of Saturday, March 24, around 300 people of all ages gathered in a public park in Marshall County for the Marshall County/Western Kentucky March for Our Lives. They held onto signs and umbrellas as they crowded around a covered stage where a group of students and other speakers sat, and they protested against gun violence.

When it was her turn to speak, Hailey Case, a Marshall County freshman, stepped behind the microphone.

“School shootings were basically taboo to talk about before the students of Parkland decided to stand up,” Case said.

People in the audience clapped. Case continued.

“We look to our government, to the adults of this nation, to keep us safe. We trust them to save our lives because that’s what they promised to do. We trust them to always put us above everything else because that’s what they said they’d do. But they didn’t.”

Case had been particularly nervous to address the crowd, but as she did, the audience supported her, listening intently and cheering her on as she spoke. And no one seemed to disagree with her. There were no counter-protestors present this rainy Saturday in the park.

One by one, each of the speakers at the event — many of whom were students at Marshall County High School and present the day of the shooting — addressed the crowd and told their stories.

Keaton Conner and Cameron King were sitting in their cars in the school parking lot, waiting for one of their friends to arrive so they could all walk into the school building together. Fifteen-year-old Lily Dunn, a freshman, and her sister were running late.

“I will forever be grateful we were late to school that day,” Dunn said from the stage. “My friends, family and community will never be the same.”

Before the demonstration ended, the emcee grabbed the microphone to make one last announcement. He encouraged the crowd to vote in the upcoming primary election in May and the general election in November, and he reminded the students that they could go ahead and register to vote if they were 17, as long as they’d be 18 by the election in November.

As he said this, one of the speakers, 17-year-old MaKayla Wadkins, a senior at Calloway County High School, looked over at a friend as a smile stretched across her face. Together, they stepped off the stage where they’d been sitting and rushed over to a booth that was set up to register voters nearby.

Wadkins, who would turn 18 in June, told the Kentuckians for the Commonwealth organizers running the voter registration table that she hadn’t known she could register to vote now.

“I had no idea,” she said as she grabbed a clipboard and a pen and started filling out her information. She said being able to do so was “empowering.”

Heather Adams said it was actions like this — young people registering to vote and heading to the polls for the first time — that would lead to true change.

“These kids now know that their voices are important and that there are actually people listening to them,” she said. “And legislators better start listening because, if they don’t, they’re going to get voted out before you know it.”

But Adams and the group at the March for Our Lives demonstration weren’t the only ones trying to make a change. Across Marshall County, others continue to try to improve their community — whether by advocating for gun reform, debating the best ways to improve school safety, raising money for those affected by the shooting or pulling one another in close.

Months after the school shooting that shook Marshall County to its core, residents of this mostly conservative county and surrounding communities, like much of the rest of the nation, are being forced to grapple with the ugly reality of gun violence and school shootings. Differences of opinion and debate persist. Scars and grief remain evident.

But still, light shines through the darkness — much like the soft glow of the candles community members held two days after the school shooting — leaving some with hope for the future.

“I hope that we can be remembered as a school that went through something terrible but came out even stronger,” Conner said. “… I hope whenever people hear about us, they feel inspired, not sad.”