By Skyler Ballard

Hallways are abnormally empty during the last week of classes at Parker-Bennett-Curry Elementary School as testing commences. Sharpened pencils and test packets lay in wait on desks. The small black lines of a barcode in the corner of the packet translate into students’ defining characteristics: name, age, race, socioeconomic status, test score.

Those test scores are extremely important for Parker-Bennett-Curry, a diverse school located in the middle of the Housing Authority of Bowling Green, Kentucky. It is considered by the state to be a “focus school,” scoring in the bottom 10 percent of the state.

It is also considered a minority-majority and high-poverty school, with nearly all of its students under the poverty line. Parker-Bennett-Curry faces one of the biggest issues in American education: the achievement gap.

The achievement gap refers to the disparity of performance between groups of students, especially groups defined by socioeconomic status, race, and ethnicity. At Parker-Bennett-Curry, the gap could not be more pronounced.

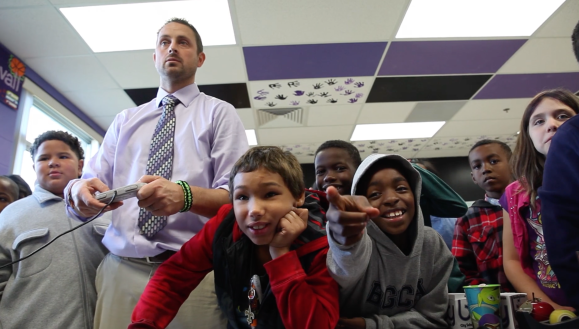

“Every student we have here is technically at risk,” said Jonathan Stovall, a fourth grade teacher at the school in his tenth year as an educator. “There is something about their life that puts them into that category, whether it’s socioeconomic status, minority status, or life experiences.”

This gap and the factors that go into it have been an issue of focus in education for as long as public schools have been around. Educators have long been trying to solve the problem, and in recent years, test scores across the nation have been seeing some improvement.

However, behind the rise of the test scores hides the widening gap between performance of minority and low-socioeconomic students.

The gap based on demographics and English-language proficiency

Demographically, Parker-Bennett-Curry varies from most schools in Kentucky, with only 18.8 percent white students compared to a state average of 78 percent, according to the school’s 2015-2016 report card distributed by the Kentucky Department of Education. Of that, 40.1 percent of the school’s students are African American and 27.6 percent are Hispanic, compared to a state average of 10.5 percent and 6.0 percent respectively.

Jeffery Morning, a guidance counselor at Bardstown Middle School in Bardstown, Kentucky, believes that a large portion of the racial achievement gap stems from teachers themselves.

“I come from a gap situation myself as a black man and I relate to the problem looking at how I grew up,” said Morning. “But the majority of teachers out there can’t relate and that’s why minority students aren’t getting the attention they need in school.”

Morning believes that the problem lies in teachers not understanding cultural differences when it comes to race as well as teaching English Language Learners, or ELL, students.

When Marvin Picado sat in Morning’s social studies class his freshmen year of high school, he was still having more trouble than his classmates with written assignments.

With a mother from Nicaragua and father from Costa Rica, Picado’s first words were Spanish. Growing up, his family mostly spoke what he refers to as Spanglish, a mix between English and Spanish. In middle school, Picado failed his English as a Second Language (ESL) test.

“I remember thinking the test was really hard even though I could speak decent English by then,” Picado said. “I always felt a little behind.”

Picado isn’t alone. There is a drastic difference in test scores from ELL students and their counterparts, which Morning believes is up to educators to solve.

The gap based on socioeconomic status

According to the Kentucky Department of Education report card, 95.7 percent of Parker-Bennett-Curry students receive free lunch based on the National School Lunch Program (NSLP), compared to a statewide average of 55.4 percent. According to NSLP, “children from families with incomes at or below 130 percent of the poverty level are eligible for free meals.”

Beyond statistics, educators are aware of the difference between affluent and less privileged students. According to Stovall, often times students of lower socioeconomic status are not as exposed to resources as their middle and upper-class counterparts.

“Experiences are a big deal in education and kids that have a lot of experiences in life tend to have a lot of prior knowledge,” said Stovall. “Students that don’t have a lot of experience outside of a few streets tend to not have such knowledge, like these kids.”

These environmental factors, referred to as “opportunity gaps” greatly effect students’ performance ability.

According to The New York Times, “children of less educated parents suffer higher obesity rates, have more social and emotional problems and are more likely to report poor or fair health. And because they are much poorer, they are less likely to afford private preschool or the many enrichment opportunities — extra lessons, tutors, music and art, elite sports teams — that richer, better-educated parents lavish on their children.”

“It’s just different. Kids here go to the boys and girls club after school and in the upper class, kids go to the country club,” said Stovall. “These kids are measured by standardized tests but they don’t live standardized lives.”

Fighting for a better future

With the hidden numbers of test scores and the achievement gap widening, educators are determined to close the gap as much as possible.

Delvagus Jackson, the principal of Parker-Bennett-Curry, believes that bridging the gap is in the hands of educators.

“It’s all about us being role models that our students can look up to,” said Jackson. “Many times, we’re standing in that gap for parents.”

For Morning, its building a relationship with both the students and their parents that will help close the gap.

“Students perform better when they feel an attachment to school,” said Morning. “Most kids that are on the lower side of the gap, who are minorities or under-privileged, don’t have that connection often because its not emphasized in their home life.”

For Stovall, improvement starts with creating a love of learning as well as incorporating reading into every subject area. The goal of Parker-Bennett-Curry during this year’s testing week is to move up from a novice to a proficient rating, eliminating their status as a focus school.

“We try to keep these kids interested in wanting to learn and continuing their education to make it valuable,” said Stovall. “If we can create that love, the achievement gap might not completely disappear, but I think it will decrease.”